The Power of Monopsony

I work at a public university. Like many such institutions, we have been dealing with reduced support from the state. In fact, the percentage of the school’s budget that is funded directly by the state has fallen from 50-60% in the 1970s to about 10% (I think it’s less than 10% currently). The school has had to increasingly rely on tuition hikes in order to fund itself. This, of course, is increasingly unpopular with students. No longer can they attend their home state public university at a reasonable cost. In-state tuition is about $12,500 before room and board, about three times more expensive in real terms than in the mid-1980s. Out-of-state tuition, on which the university relies heavily has also seen similar increases. So the only public university in the state receives about 2.4% of the state’s total expenditures.

This seems like a bad idea. In a world in which economic success increasingly relies on completing some level of higher education, the state is not investing in the human capital it will need to grow in the future. Parents and students are upset. Professors and administrators are upset. This doesn’t seem like a political equilibrium. And yet the trend continues. The question, then, is why?

I believe that the answer is the rising cost of health care and specifically the larger and larger percentage of the budget taken up by Medicaid. Medicaid expenditures, of which the state pays slightly less than half of the total (the Fed picking up the rest), now account for 30% of the state’s total budget. This, of course, is up from 0% in the mid-1960s. As Medicaid eats up a larger and larger piece of the budget pie, everything else has to shrink.

So what do we do? I suppose one solution would be to leave our poorest and most vulnerable citizens without access to health care. But I don’t believe that would be the best solution. Instead, we should look at the best way to control our health care costs. And this is where the power of monopsony comes in. A monopsony is like the opposite of a monopoly. In a monopoly, there is only one seller. That seller can maximize its profit by increasing its prices and reducing its output compared to what would exist if there was more competition. In a market with a monopsony, there is only one buyer. That buyer can reduce the sellers’ profits by paying less than they would have to in a more competitive market.

Now normally, I wouldn’t encourage either monopoly and monopsony in any market. But the health insurance and health care markets are not like any market. They are fraught with problems of adverse selection, moral hazard, and information asymmetries. These markets, left on their own, will fail to achieve efficiency 10 times out of 10. That’s where monopsony, in the form of a national, single-payer health plan comes in.

With single-payer health care, everyone is enrolled and pays for it through a tax (similar to Medicare). Out goes adverse selection and moral hazard. The government is in the position to provide information on the efficacy of treatments and only pay for those that work. And the single plan is in a position to bargain prices with doctors, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies to keep costs low.

The United States spends more than twice as much per person on health care than the median OECD country. And it does so without getting better results. If we adopted a single-payer plan, the potential savings would be measured in the trillions of dollars. We could increase funding to public education (that’s where we started) and infrastructure and everything else that’s being starved. What’s not to like?

Always remember that one person’s spending is another person’s income. Spending $1 trillion less on health care each year means $1 trillion less in income for doctors, nurses, hospital staff, and pharmaceutical workers. This would have to be a gradual process just so we didn’t throw the economy into recession. But these groups will fight tooth and nail to protect their incomes. Bargains will have to be made. I would start with paying off education loans for health care workers. It may also be a good idea to throw more federal research money to the pharmaceutical companies.

But it doesn’t make sense to allow one industry, even one as important as health care, to eat up more and more of our resources if we don’t have to. The power of monopsony would allow the federal and state governments to spend less and less on Medicare, Medicaid, and other health programs, opening up money for investing in the areas that strengthen our economy for the future. What kind of suckers are we that we don’t do this?

Sovereign Debt and Eurozone Exit

So my previous post ignored the 800-lb gorilla in the room, namely sovereign debt. The goal of exiting the eurozone would be to make your economy more successful and allow monetary policy that is appropriate for your national economy. If successful, this will lead to reduced unemployment and higher tax revenue. It will not solve chronic deficits.

So I believe that sovereign debt should be converted from euros to the new national currency at the shadow exchange rate. This would avoid a European-wide banking crisis as investors should be indifferent between the old debt in euros and the new debt in lira (or pesetas or drachmas). But it wouldn’t solve the Greek problem of continuous deficits due to overspending and poor tax collection. I don’t believe there is any monetary solution to that issue. It should, however, greatly help countries like Spain and Italy which have not been financially profligate.

How to Break Up the Euro

Let me start by saying that this is completely outside of my area of expertise (assuming I have one). But sometimes an outsider’s perspective can be useful. And because a breakup of the eurozone seems increasingly likely, here is my suggestion on the best way to accomplish that.

The problem, as I understand it, is that euros are completely mobile within the eurozone so that if Greece (or Spain or Portugal or Italy or Ireland) looks like it’s about to leave the currency in favor of the drachma, everyone will take their euros out of Greece and put them in Germany. Then as the drachma depreciates against the euro, they can exchange their euros for drachmas without losing their real purchasing power (and even increasing it within Greece). This will cause a banking crisis making the exit extremely painful.

So we have two related problems with which we have to deal. First, how do we keep the euros from flying out of the countries that are most likely to leave the eurozone and adopt a new national currency. And second, how do we price those new currencies against the euro. The problem is that we’ve been assuming that we can’t do the second until the countries have left the euro, making a solution to the first problem seem impossible.

The solution requires that we price the potential new currencies (against the euro) before any countries actually leave. If the new drachma (or peseta or lira or Irish pound) is priced appropriately, there will be no desire to move euros around. For example, let’s say that in order to get Greek prices back in line with the rest of Europe, the new drachma would have to depreciate 100% so that the exchange rate would be two drachmas per euro. If that’s the “correct” real exchange rate, so that the purchasing power of two drachmas in Athens is the same as one euro in Frankfurt, then people will be indifferent between having two drachmas and one euro. If Greek depositors know that they will get two drachmas for each euro in their account, then they will have no incentive to move those deposits to Frankfurt before conversion.

The goal of this plan is to create a shadow exchange rate for each country within the eurozone (although it’s especially important for those most likely to leave). This way you know that you’ll get two drachmas for every euro or 1.3 pesetas or 1.5 Irish pounds. This would keep the capital in the troubled countries because depositors and investors would know that their value was safe.

How do we do this? We need to create a market for these nonexistent currencies. While I’m not 100% sure about the best way to do this, I do have a suggestion. I suggest that we create dual-track eurobonds. The first track would be straightforward bonds of varying durations. The interest rates would be determined by auction as in most bond issues (again, this isn’t my field, but this is my understanding of how things work). The second track would take the interest rates from the first track, but would introduce the possibility of being paid in euros or a new national currency. The exchange rate would be determined by auction in the same way that the interest rates were determined for the standard bonds.

For example, let’s say the regular 1-year eurobond is paying 2% interest. If you buy a €1,000 Greek 1-year eurobond at an exchange of 2 drachmas to the euro, there are two payout options. First, if Greece stays with the euro you will get your €1,000 plus 2%, or €1,020. It will behave just like the standard bond. However, if during that year Greece exits the eurozone, you would get paid in drachmas. In this case your principal would be ₯2,000 and with 2% interest you would receive ₯2,040 (is that the right symbol for the drachma?).

These shadow exchange rates would be public information so that every depositor and investor would know how many drachmas she would receive for every euro in a Greek bank or in exchange for euro currency in Greece. So how would an exit from the eurozone work? First these bonds would be set up, ideally for each country in the eurozone, but certainly for those countries most likely to leave (Greece, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Italy). The bonds will then tell us how much depreciation each currency would need in order to keep investors indifferent between holding euros and drachmas. It would then be up to each national government to decide whether or not to stay in the eurozone or adopt a national currency.

If the country decides to leave the euro and adopt the national currency, this is what I assume would happen: The exchange rate is determined by the national eurobonds. On the day of the conversion, bank deposits and other financial investments (including the national eurobonds) within the country are switched automatically from euros to the new currency. If the exchange rate is 2 drachmas per euro and you had €5,000 in your account, you now have ₯10,000. All prices within the country (including wages) are switched one-to-one to the new currency. That is, if you were earning €30,000 in Greece as a school teacher, you are now earning ₯30,000. If a bottle of Greek retsina cost €10, it now costs ₯10. So the real wage for domestically produced goods stays exactly the same. But of course the cost of imports will rise and the cost of exports will fall (remember, that’s why we’re doing this in the first place). A BMW that used to cost €20,000, or 2/3 your annual salary will now cost ₯40,000, or 4/3 your annual salary. On the other hand, that €10 bottle of retsina will now only cost €5 in Frankfurt. And Germans will find a vacation in Greece to be much cheaper than before. This should boost Greek exports and employment.

The whole key to this plan is that we don’t know what the exchange rate should be. We know it isn’t 1:1. That’s why we’re having this problem in the first place. But we won’t be able to figure it out. We need to use the market, investors with real money on the line, to figure out the appropriate rate. Maybe it’s 1.2 drachmas per euro, maybe it’s 1.5. I have no idea. But if investors are willing to buy the national eurobonds, this means they are indifferent between euros and the new currency at that rate.

Will people be able to game the system? I’m not sure. Let me know. I’m sure that international finance people will be able to improve this plan, but we need a plan to minimize the chaos that a breakup of the euro will otherwise entail. I think this would help.

Is “Inflation…always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”?

Milton Friedman famously said that:

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon…

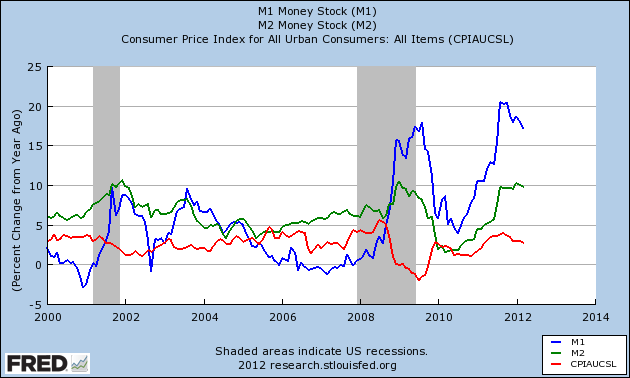

But that doesn’t seem to be the case recently:

The blue line is the annual percent change in M1, the green line is the annual percent change in M2, and the red line is the annual percent change in the CPI, or inflation. Inflation has remained muted while the money supply has increased dramatically over the last 4 years. The correlation between the percent change in M1 and the CPI is -0.48 and between M2 and the CPI is -0.19. Nonetheless, monetarists tell us to worry about inflation.

But is this really what Friedman meant? I don’t know, but Wikiquote gives us a more complete quote than I’ve given above:

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.

So what he seems to be saying is what seems to be the obvious truth that you can’t have inflation without an increase in the money supply. What he isn’t saying, at least in this quote, is that you will always get inflation with a large increase in the money supply. After all, if the money is not spent, then the price level won’t go up. And that seems to be the case recently. People and (especially) firms are hoarding money, mainly in the form of checking accounts, but also a bit in the form of currency. When they start spending again, the Fed is going to have to do some quick work to avoid inflation, but it certainly won’t be impossible.

Maybe I’m missing something obvious. After all, I’m not a monetary economist. But it seems to be like inflation is mainly caused by higher aggregate demand (along with things like indexation). It can be controlled by tightening monetary policy, but it can’t be produced by simply increasing the money supply.

That’s why I don’t really get the whole NGDP targeting argument. The argument, as I understand it, says that when real GDP growth is lower than the Fed would like, it should accept higher inflation. But low AD leads to lower inflation. How is the Fed supposed to get to 5% inflation in today’s economy? The money supply (M1) has increased by over 50% since 2007 and inflation has stayed well below 5%! What is the Fed supposed to do?

Really, I’m asking.

Republican “Intellectuals” View Life as a Game

Alec MacGillis writes about Mankiw’s defense of the tax treatment of carried interest. At the end he (doesn’t) link to Matt O’Brien who links to a Mankiw blog post saying the exact opposite.

This is what I mean when I say that those academics and other public intellectuals on the right view this whole thing as a game. It’s not about doing what’s right and it’s not even about doing what you believe to be true. It’s about confusing the issue so that your masters can do what they want.

But it’s not a game. Allowing hedge fund managers to pay 15% in federal income taxes instead of 35% robs the Treasury of much needed revenue, putting a burden on current and future tax payers. It also increases inequality in a way that simply didn’t happen fifty years ago.

The Needed Assumptions of DSGE

Noah Smith has a great post on whether or not macroeconomic models are biased in one political direction or the other. He reaches the (correct, in my opinion) conclusion that they do have a conservative bias, mainly because they are so simplified that there can be no useful role for government.

I think the most useful post is the list of assumptions in the original Kydland and Prescott Real Business Cycle paper. With so many assumptions, that model is basically useless. Smith goes on to point out that if you relaxed even the ones that are most problematic (in my opinion: representative agent modeling, rational expectations, and flexible prices) you quickly get a model that is completely unwieldy.

Why so use these models at all? They are mathematically complex, they are micro-founded (sort of), and they give little to no role for government.

Personally, I didn’t like these models when I learned them, and I still don’t find them useful. Give me a partial-equilibrium model with a little more realism any day.

Libertarians and Feminism

I just came across two different posts that show libertarians uncomfortable stance toward feminism. The first was from Noah Smith showing that Peter Thiel thinks that allowing women to vote was a bad thing (at least for libertarians).

The second was from Mike Konczal that showed how uncomfortable women’s rights and female sexuality made Ludwig von Mises.

From a purely philosophical point of view, you would think that libertarians would welcome feminism as it increased the amount of freedom in the world by opening up new opportunities and giving new rights to half the population.

But libertarians (often, not always) seem to worry about protecting the rights and liberties of themselves and people like them, rather than extending them to others. Thus we end up with misogynistic and racist white male libertarians. One question is how women and minorities can feel comfortable in these groups.

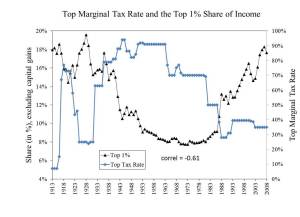

The Relationship Between Marginal Tax Rates and the Top 1%

Over the last (almost) 100 years the United States has had widely different approaches to very high income in its tax code. In 1913 the top marginal tax rate was only 7%. By 1918 it was 77% before falling in the Roaring 20s down to a low of 24% in 1929. The Great Depression lead to another steep increase and the top marginal tax rate never dipped below 63% until the Reagan Revolution in 1982. For much of the 1950s it was over 90%. Now, the top income level to which the tax applied was much higher (especially in real terms) than it is now. But during the strong growth of the 1950s we asked our richest individuals to fork over $0.90 of the last dollar they earned.

At the same time, we have seen widely different shares of wage and salary income going to the top 1 percent of earners over those (almost) 100 years. According to Piketty and Saez, it reached a pre-Depression high of 18.4% in 1928. That fell fairly steadily down to a mere 7.7% in 1973 before returning to 18.3% in 2007 (it has dipped slightly during this Lesser Depression).

Putting these two measures on the same graph makes it look a lot like they are closely related.

The correlation is -0.61. When the tax rate goes down, the share of income going to the top 1% goes up, and vice versa. Is it possible that one is causing the other? Or that there’s something else causing both? On the other hand, is it possible that they aren’t related at all?

Assuming there is some sort of causal relationship at work, I can think of a few possible explanations. Deciding which one is correct is not so easy.

- Rich people don’t work as hard (or as much) when marginal tax rates are high, reducing their income.

- This is certainly possible. If I had to pay 90% of my last dollar to the government, I would definitely consider not working quite so much.

- And this is one argument against high marginal tax rates. It reduces the incentive to work and therefore will hurt overall economic growth.

- But there doesn’t seem to be any relationship between higher top marginal tax rates and economic growth. In fact, if there is any relationship, it looks like it is positive, at least until you get to about 70%.

- Rich people hide more of their income from the IRS when marginal tax rates are higher.

- I’m told that there was evidence of this in the 1950s and 1960s. And again, I’m sympathetic. 90% is a lot of money to hand over to the government on that last paycheck.

- But one question then is how much they hid, and how much they stopped hiding when marginal tax rates came down. Specifically, was it enough to increase federal revenue?

- The answer seems to be maybe. There is almost no relationship between Federal tax revenue as a percent of GDP and the top marginal tax rate.

- Very high marginal tax rates serve as a signal about what society views as acceptable top incomes.

- This is fairly speculative, but the idea would be that a top marginal tax rate of 90% says to CEOs and finance professionals that we don’t think anybody should earn above a certain amount.

- So if we set the highest marginal tax rate at $10 million (or $20 million, or $50 million), then we’re saying that there’s no point in having an income higher than that. After all, going from $10 million to $100 million in gross income only increases take-home pay to $19 million.

- I think the interesting question is what this would do to everybody else’s salaries. Would they fall due to lower economic growth? It doesn’t look like it. Would they increase? I’m not sure.

The CBO Makes the 99%’s Point: They’re Eating Our Pie!

The CBO very thoughtfully made what I believe is the main point of the OWS protesters. The main income growth over the last 30 years has gone to only the top 1 percent of the income distribution, leaving everybody else only marginally better off than we were three decades ago.

The growth in (after-tax!) income by quintile is striking:

Growth in Real After-Tax Income from 1979 to 2007

Source: Congressional Budget Office

The first four quintiles have seen less than 50% growth over 30 years, or less than 1.4% per year. And as you can see that’s much smaller for the bottom 40% who have seen income grow less than 1% per year. Meanwhile the top 1% has seen after tax income grow by 270% over the same time period, or 3.6% per year.

That means that every group except the 1% have seen their slice of the American pie shrink between 1979 and 2007.

Shares of Market Income, 1979 and 2007

Source: Congressional Budget Office

I’m just glad that the 99% is finally waking up and demanding that we do something about it. So while I’m no protester (I’m much to soft and squishy), here are a few suggestions:

- Increase the marginal tax rates, especially on the top 1% (my next post will expand on this).

- Put a Tobin tax on financial transactions, say $0.05-$0.10 per share (or the equivalent).

- Pass a constitutional amendment that says all federal elections are to be financed with only public funds.

Growth in GDP per capita comes from the entire economy. It comes from businesses competing for your dollar and coming up with new products and better ways to make old products. It can be strong when the top marginal tax rate is 90% (as it was in the 1950s) or when it is 39% (as it was in the 1990s). It can come when the top 1% is getting 7% of the national income and when it is getting 15% of the national income. We simply have to choose which world we want to live in.

I believe the three suggestions above will slow the growth of the top 1 percent’s income, reduce the size of the financial sector, and make the government more accountable to voters rather than those who donate. That’s the world I want to live in.

What Do Unions Do?

Public unions have been taking a lot of heat from the right recently, while private sector unions continue to diminish in importance in the United States. I think it’s useful to think about what unions actually do in order to think about whether they are harmful or beneficial (or neutral) to economic performance. In order to do that, I want to do a little thought experiment.

Imagine an employer and a potential employee. While there is some doubt about how productive the worker will be at this particular job, the expectation is that there will be some value created by the match. That is, for every employer-employee combination, the worker creates a certain amount of value added for the firm. If the firm decides to hire this worker, the next step is to figure out how much to pay her.

The firm will not pay more than the value of that the worker can provide. If it did, it would lose money every day. The worker, on the other hand, will have some reservation wage below which she will choose not to take the job. It could be equal to the value she places on leisure or it could be the value of her next best job offer. If the firm offers to pay her less than this reservation wage, she will politely decline and go to her next best option.

So let’s call the reservation wage r and the value that the job creates v. In a search type model (a la Mortenson-Pissarides) we throw these numbers into a Nash-bargaining black box and come up with some equilibrium wage. But there could be a large number of possible equilibria. It depends on the bargaining power of both the firm and the employee which in turn depends on the tightness of the labor market for the employee’s particular skills.

In general, most workers have significantly less bargaining power than the firms that want to hire them. Therefore wages tend to much closer to r than to v. There are, of course, exceptions. NFL quarterbacks, CEOs, and airline pilots spring to mind. But for factory workers, clerical workers, retail workers, and most of the rest of us, the firm generally has the upper hand in bargaining over wages and can make take-it-or-leave-it offers. While some industries may pay efficiency wages above their workers reservation wages in order to reduce efficiency, many do not.

Firms then, are often able to capture much of the surplus that is created by each employer-employee match. When we see corporate profits increasing while labor income is stagnating or decreasing, this is evidence that firms have been successful in reducing the amount of the surplus that goes to labor. That we have seen this recently in the United States is no surprise because we have also seen the power of labor unions fall.

For what do labor unions do? At least when it comes to wages, they are able to increase the bargaining power of labor. This allows workers to capture more of the surplus created by these employer-employee matches and push wages closer to v. This will reduce corporate profits and increase the share of revenue that goes to labor. This is what we saw in the 1940s and 1950s, the heyday of union growth in the U.S.

But the question remains whether this is good or bad. We have seen a number of industries that seem to have given away too much to labor. leading to a loss of profitability and competitiveness and even bankruptcy. The answer to this question is, unfortunately, far from clear. First of all, increasing the bargaining power of labor is definitely good for (currently-employed) workers in the short term. It will increase their wages (and other forms of compensation). Of course, by raising the cost of labor, it will likely lead to fewer jobs in that particular firm/industry. Firms have a downward sloping demand curve for labor, so when the price goes up, they will employ fewer workers.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that it is bad for the economy. Increasing the share of income that goes to labor (as opposed to profits), leads to increased consumer spending and higher demand for firms. In the end, it may lead to more total employment in the economy or it may simply be neutral. Certainly the economy of the 1940s-60s was no worse than the economy of the last 20 years and it may have been healthier.

But what of the long-term consequences? If firms that are profitable now give away too much to the unions, they may find themselves uncompetitive in the future, needing to cut jobs or even declare bankruptcy. Certainly the U.S. auto industry seems to be in this position and unions have had to give back a fair amount of what it won in the past in order to keep the big three auto companies afloat.

Here, I believe, unions need to think more like the owners of the firms than as representing the interests of the firms’ most important input. The surplus value created by each employer-employee match is not fixed in stone. It will vary over the business cycle and it will vary over time as the competitive landscape of industries change. If labor unions understand this, they can bargain for contracts that accept this fact and that increase pay to labor when the firm is doing well and decrease it when the firm is struggling. This is often how the pay is structured for those workers that have more bargaining power to begin with (think CEOs).

The obvious solution, which has been proposed again and again in the history of labor economics, is some form of profit sharing and/or employee ownership. A Ford that has lower base pay for workers but that regularly shares its profits across the board will be a much more competitive firm than a Ford that faces a UAW intent on extracting as large a share of guaranteed pay as possible. Of course, in a world in which workers own a large percentage of each firm, it would be inappropriate to have industry-wide unions like the UAW which might see it in the interests of its members to reduce competition in order to increase profits and pay.

Public unions, in this scenario, represent a problem. After all, they do not exist in a competitive world trying to maximize profits. If they work for anybody it is the citizens of the country, state, city, or town. These citizens have an interest in having high quality service at a low cost so that taxes are held in check. Politicians, on the other hand, elected to negotiate with these workers often have their own agenda. They may be more willing to make concessions in the interest of labor peace, especially if the bill for those concessions won’t come due until they have been out of office for a long time (think defined-benefit public pensions now bankrupting states and municipalities across the country). Or they may be intent on breaking the unions for ideological reasons especially if they have been sent to office by business interests intent on lowering their own labor bill.

It is therefore very important that public-sector negotiations take place in as public and open a format as possible. For the most part, voters and taxpayers want to see their teachers, police officers, firefighters, and other public servants paid fairly. What they don’t want is to see promises made that are much more generous than the compensation they themselves receive, as the taxpayers will eventually end up footing the bill.